A systems thinking approach

Systems thinking is a mental framework that helps us to become better problem solvers. Systems thinkers find ways to shift or recombine the parts in the system that offer an improved outcome.

The Prevention Centre delivers internationally significant knowledge about the application of a systems-based approach to the prevention of chronic disease.

Page contents

What is systems thinking?

Systems thinking is defined as a way to make sense of a complex system that gives attention to exploring the interrelated parts, boundaries and perspectives within that system.

Rather than a systematic approach, system thinking takes a systemic approach. Research can be more effective if you use a balance of both the systematic and systemic approaches.

We introduce the idea of taking a flexible approach in the short video below, written by Melanie Pescud and Lucie Rychetnik based on empirical case studies and the Systemic-Systematic duality described by Ison and Straw. The Hidden Power of Systems Thinking: Governance in a Climate Emergency. (2020)

How can systems thinking and systemic approaches help?

Systems thinking is useful because it can:

Systems thinking and chronic disease prevention

Work in chronic disease prevention, and public health more generally, has targeted individual behaviour, but many factors, including where we work, eat, play and live, and our access to work and education, all affect our health.

It is not enough to simply urge Australians to eat better and exercise more. We need to look at the wider systems that directly impact on our health or can help or hinder behaviours that cause chronic health problems. We need to look in depth at our communities, our food systems, our environments and workplaces and how each of these interacts to create communities in which healthy behaviours are the easier, more sustainable options.

Systems thinking helps us to look at these wider systems. Rather than just tackling the tip of the iceberg, a systems thinking approach delves below the surface and identifies the fundamental and interconnecting causes of complex issues such as chronic disease.

We asked systems thinking experts to explain their perspectives and provide insights into why they use a systems approach in chronic disease prevention research.

Systems change frameworks

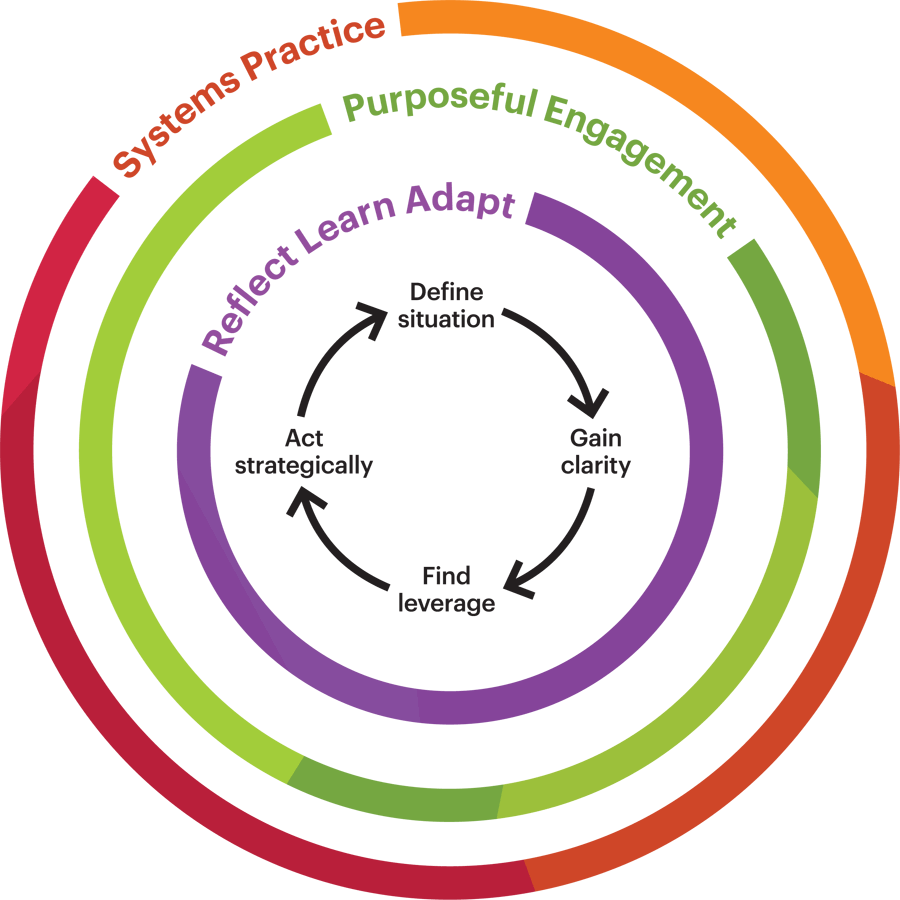

The Prevention Centre has developed two frameworks for systems change.

-

Systems change framework

This report offers a general structure and process for understanding and engaging systems change efforts. -

The Prevention Systems Change Framework

This guide for prevention research and practice poses a series of questions that support teams to move from understanding systems towards implementing impactful actions.

What can systems thinking contribute to public health?

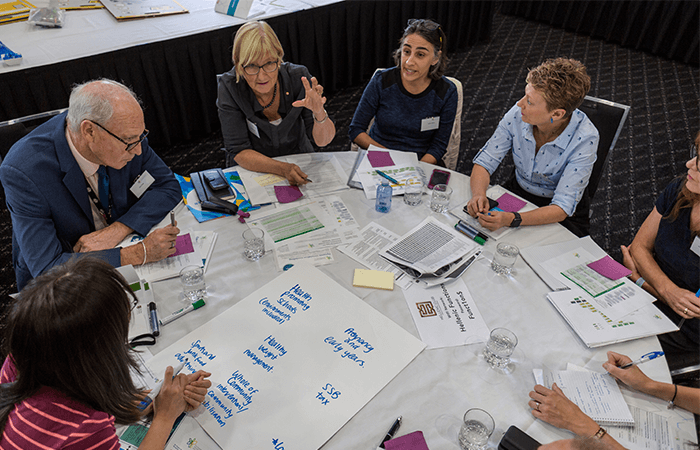

Policy makers and practitioners working to prevent chronic disease are using system thinking and systems science methods to better understand complex public health problems and inform their decision making about how to intervene. For example, participatory system dynamics modelling uses a range of evidence sources and data to map and model complex problems, engaging academics, policy experts, practitioners and community members in the process. This results in a co-designed decision support tool that can simulate and compare the likely impact of a range of intervention and policy solutions.

System dynamics modelling and the underlying theories have the advantage of allowing decision makers to experiment with different scenarios and policy options before they are implemented to reduce the risk of negative consequences and unexpected outcomes.

Models can be used to experiment with different intervention combinations to forecast their impact on alcohol-related emergency department presentations, chronic disease prevalence over time, and cost implications for the health system.

Examples of projects using system dynamics modelling for improving public health

Principles in systemic theory

How and when should systems theory be used?

Our systems project is identifying and collating key lessons on the use and value of systems thinking, systems practices, and systems science tools in applied prevention research. Using Prevention Centre projects as case studies, this research will illustrate how researchers, policy makers and practitioners can use systems approaches to better work together to bring about change. It will inform policy makers and funders of the key factors that support the use of effective systems approaches, and when, and in what combination, these approaches are appropriate for prevention research.

How can I use systems theory in practice?

In undertaking systems thinking activities, we want to have the capacity to see and sense a system, that is, patterns, structures, relationships, boundaries, feedback loops and unintended consequences of actions. This means regularly reflecting on our assumptions and mental models and exploring unintended consequences of actions and how we listen and learn from other perspectives. These practices will enhance our capacity to see and sense the system when we engage with specific tools such as causal loop diagrams or systems mapping.

Download a PDF flyer on practices you can use in your everyday systems work.

Complex is not the same as complicated

Challenges can arise when problem-solving approaches that are useful for complicated problems are applied to complex problems. This can often result in quick fixes that fail to recognise and intervene in the root causes of problems. It can also lead to new or worse problems because we have failed to understand the relationships between parts in the system.

By recognising the complex nature of the problem, and applying systems thinking approaches, investigations can delve below the surface and identify the fundamental and interconnecting causes of the complex issue – such as the patterns of behaviour, the underlying structure and the beliefs of the people and organisations responsible for creating that complex issue.

Download a PDF flyer on why complex is not the same as complicated and what this means for how we approach complex problems.

Systems thinking tools and resources

- Journal article: Leadership for systems change: Researcher practices for enhancing research impact in the prevention of chronic disease

- Blog: Creating systems of leadership in prevention research by Dr Melanie Pescud

- Blog: Pig on the Tracks by Luke Craven

- Book: Growing wings on the way: systems thinking for messy situations

- Book: Systems concepts in action

- Book: Wicked solutions: A systems approach to complex problems

- PDF: Systems thinking tools: a users reference guide

- Book: Community-based systems dynamics

- Software: STICK-E

- Software: System Effects

- Video: Systems thinking

- Article: Systems methodology

- Book: Systems thinking for social change

- Website: The systems thinker

- Report: Systems-based approaches in public health: Where next?

Book: Systems Practice: How to Act in a Climate Change World

Book: The Hidden Power of Systems Thinking

Book: Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health

Book: Thinking in systems: A Primer

Book: Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity

Journal Article: Places to intervene in a system

Journal Article: Learning in and about complex systems

Website: Stanford Sociological Innovation Review

Website: Systems Change Academy

- Report: Greater than the sum: Systems thinking in tobacco control

- Journal Article: Four-year behavioral, health-related quality of life, and BMI outcomes from a cluster-randomized whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity

- Book Chapter: Systems and Evaluation: Placing a Systems Approach in Context

- Website: Systems grant making resource guide

- PDF Report: Funding systems change: Challenges and opportunities

- Report: Systems grant-making resource guide

- Article: Leveraging grant-making

Videos and podcasts: Experts talk about systems thinking

-

How a wellbeing economy approach could promote health equality for future generations

Resource category:Podcasts

Date -

Systems thinking in the community: Nothing about us, without us

Resource category:Podcasts

Date -

Systems thinking across disciplines: Working, moving and living within systems

Resource category:Podcasts

Date -

The past, present and future of chronic disease prevention research

Resource category:Podcasts

Date -

Why prevention policy is better than cure

Resource category:Podcasts

Date

-

Global impact to local action – top 5 lessons from driving systems change

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Creating systems change for physical activity

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Why use a systems approach in chronic disease prevention research?

Resource category:Videos

Date -

How can I use systems thinking in my chronic disease prevention research?

Resource category:Videos

Date -

How to measure success using a systems approach?

Resource category:Videos

Date -

A guiding principle for systems work

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Practical strategies to mobilise knowledge in complex systems

Resource category:Videos

Date -

The practice of systems change: tips from a change agent

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Five minutes with Allan Best

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Partnering for change in a complex world

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Translating systems thinking into public health innovations

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Five minutes with Professor Nate Osgood

Resource category:Videos

Date -

Integrating big data and simulation models to support health decision making

Resource category:Videos

Date